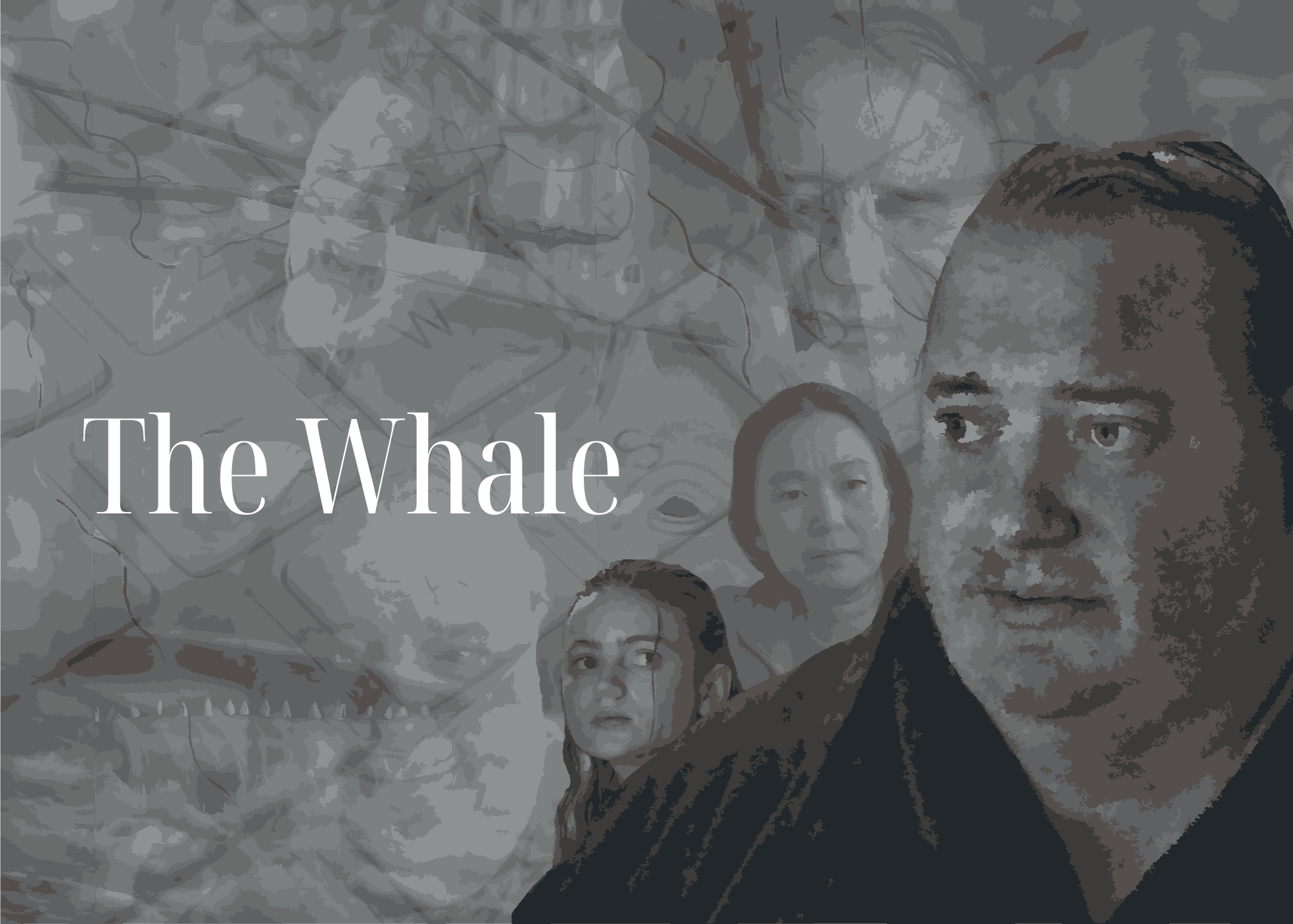

"The Whale" Review: Don't Call It A Comeback... Or A Good Movie

Brendan Fraser shines, but The Whale fails to send a message worth hearing.

ModernArt is the medium for the self-conscious. It doesn’t seem that way, primarily due to its purveyors' insistence on demeaning so-called “lesser minds” to safeguard their exploitation. The more abstract or quirky something is, the more it gets praised. If it nails the simplicity of universal concepts, it’s trite and meaningless, something only the "average" book reader, art fiend, or moviegoer would understand.

Thus, it’s difficult for "average" people to appreciate what they find in their art of choice. If the dissection doesn’t cut deep enough, their pretentious counterparts scoff at their inability to read between invisible lines. If it cuts too deeply, even without them realizing it, those same people will get defensive because they didn't pick up on the nuance. Even the smallest of details getting praised can raise an eyebrow. After all, it’s just a simple note, line, or brushstroke; why zero in on something inconsequential?

Eventually, we realize that what we gain from an artistic experience is not something to get attacked, so the attacks mean little. But what is the specific realization that allows for this confidence?

It’s simple: anything you see on a movie screen is there because someone chose it. If they wanted it, you were meant to see it; enjoying its presence makes you one with the director, composer, actor, cinematographer, etc.

Of course, the flip side is that, because of this, every choice must legitimize its own existence. We notice. We see. We react and pass judgment. If something feels out of place or unnecessary, we’ll take to it just as strongly as something we enjoy.

The Whale begins with a 600-pound man named Charlie sitting on the couch of his Idaho apartment masturbating to gay pornography. It’s a test of our sensibilities; masturbation is a healthy practice in which most people engage. Countless films have shown it, not to mention the number of times we’ve likely walked in on someone (or gotten walked in on). As we get introduced to a man we’re to spend the next 117 minutes with, the movie asks if our feelings about that introduction are born out of general discomfort or something more specific.

Are we repulsed because Charlie is fat?

The question cannot get answered because it is the first time we see the man. If our initial meeting with anyone began with them furiously stroking their penis, we’d feel put off (unless that was the intent).

It’s pointless shock value; it doesn't even set the tone for anything the film tries to develop. No matter how many times Charlie asks, gets told, or ponders whether he’s disgusting, The Whale is never about him being obese, which raises the question:

Why is he obese?

It’s a new take on addiction. Nicolas Cage claimed Oscar gold in 1996 for playing an end-life alcoholic in Leaving Las Vegas, the same addiction that’s garnered nominations for Denzel Washington (Flight), Bradley Cooper (A Star is Born), and wins for Ray Milland (The Lost Weekend) and Jeff Bridges (Crazy Heart).

We’ve seen Cate Blanchett (Blue Jasmine), Bette Midler (The Rose), and Anne Hathaway (Rachel Getting Married) secure wins or nominations for battling drug and/or alcohol addiction. Rarely have we seen someone’s binge-eating take on a life of its own on-screen.

Thus, one could argue that makes it a worthy decision, but they’d lose the debate. As Charlie gets inundated with verbal attacks from his teenage daughter, Ellie, who he abandoned for his student (don’t worry, it was a night course), pleas from his nurse, Liz, to seek medical care, and attempts at religious conversion by the young missionary, Thomas, who shows up at his doorstep in the opening scene, we realize that every choice he’s made stems from within.

As he offers his daughter money to spend time with him, rewrites her school essay for her out of desperation, and refuses to acknowledge her shortcomings in defense of his idealized perspective, it’s clear that Charlie is a man not suited for substantial personal relationships.

Look at how he and his late lover, Alan, came to be: Alan was his student and began stopping by his office hours, where they discovered many commonalities. It’s an important detail, however, that it matters to Charlie that Alan initiated, made an effort to spend time with him. His appreciation for Alan feels thin, but the birth of it has a clear origin: Charlie getting made to feel special and validated.

It makes sense. Throughout the film, Charlie frequently revisits an essay about Moby Dick, narrowing his focus on lines regarding the parallelism between the author’s inner turmoil and the novel’s goings-on. Eventually, we learn that Ellie wrote it in 8th grade. Charlie's admiration for it runs so deep that he sabotages her chances of graduating high school by submitting it on her behalf instead of adhering to her actual assignment.

He is a romantic to the core, incapable of seeing reason and logic, bound by his truth, never by what is. He flees from his family life to embrace the wild passion of forbidden love and build a life based on it. It is of little shock that when reality smacks him across the face, when Alan commits suicide due to religious guilt over his sexuality, he suffers a downward spiral.

Sadly, the story has been told a thousand times before, specifics aside. Yes, binge eating and the resulting morbid obesity is relatively new for an Oscar-bait film, but how many times can we watch someone hit rock bottom in such damaging ways before we start asking why it takes that much to make us care about a story?

Charlie is troubled not because he’s fat but because of his nature. His worldview doesn't make for a good husband, friend, or father. We must see things for how they are to do right by people; anything else is enabling. It’s no surprise that the one person who cares for him is Liz, the ultimate enabler, constantly feeding Charlie fatty foods and pushing him to get help with all the persuasiveness of a late-night infomercial.

The Whale does have other issues. It takes too long to gain momentum; for roughly 30 minutes, we can't tell what the movie wants to accomplish. The weepy strings only evoke annoyance that the film insults its protagonist by behaving like every breath he draws is a tragedy. Its insistence on being grim, from all the familial resentment, cardiac episodes, and even its gloomy aesthetic, feels more contrived than it realizes. The performances sell a middling story so well that you briefly forget the film has little substance, but it's a Band-Aid over a bullet wound.

The core issue is Charlie’s size. A man this delusional, naive, and incapable of making good choices for himself and others while possessing all the traits we praise is worth exploring. We don’t need him to be alcoholic, drug-addicted, or morbidly obese to embrace that exploration. Charlie only needs to be a man whose warped perspective ruins the people around him. It could test our idea that being “nice” matters when such qualities get contrasted with the havoc they wreak if left unchallenged or underdeveloped. It could remind us that no matter how difficult it is to accept, spice can be just as beneficial as sweetness.

We often criticize those who defy the conventional wisdom of what it means to be “good;" The Whale had the opportunity to show that the accepted definition of decency doesn’t always yield the desired result. Charlie allowed himself to get crippled by life and took the people he “loved” down with him. It’s sad: that could have meant something, but The Whale is so devoted to the idea of being fat and the broad explanation of how Charlie’s obesity occurred to care.

It’s still true: we will always find ourselves in movies, occasionally in ways we did not expect. But great films don’t rest on that and toss out a generality, hoping we latch onto it. Great movies sink their teeth into the subject matter, develop themselves, and use what may shock us to reveal something we eventually realize we should have known from the start. The Whale has been accused of exploitation, using morbid obesity to shock audiences into submission instead of lending them some genuine credence and empathy.

The Whale is exploitative, but not because it doesn’t crusade for the legitimacy of morbid obesity or do a two-hour psychoanalysis of its protagonist. It’s exploitative because it uses Charlie to make a point it isn’t prepared or willing to make, only feign concern to seem profound.

Movies like The Whale will always exist, so the repudiation, while justified, will have no effect. Just as well; if nothing else, it may earn Brendan Fraser, 2022’s comeback kid, an Academy Award, and for any millennial who grew up on The Mummy movies, there’s nothing wrong with that.

.png)

34

Director - Darren Aronofsky

Studio - A24

Runtime - 117 minutes

Release Date - December 9, 2022

Cast:

Brendan Fraser - Charlie

Sadie Sink - Ellie

Ty Simpkins - Thomas

Hong Chau - Liz

Samantha Morton - Mary

Editor - Andrew Weisblum

Cinematography - Matthew Libatique

Screenplay - Samuel D. Hunter

Score - Rob Simonsen

%20(13%20x%206%20in)%20(13%20x%204%20in).png)

.png)

.png)