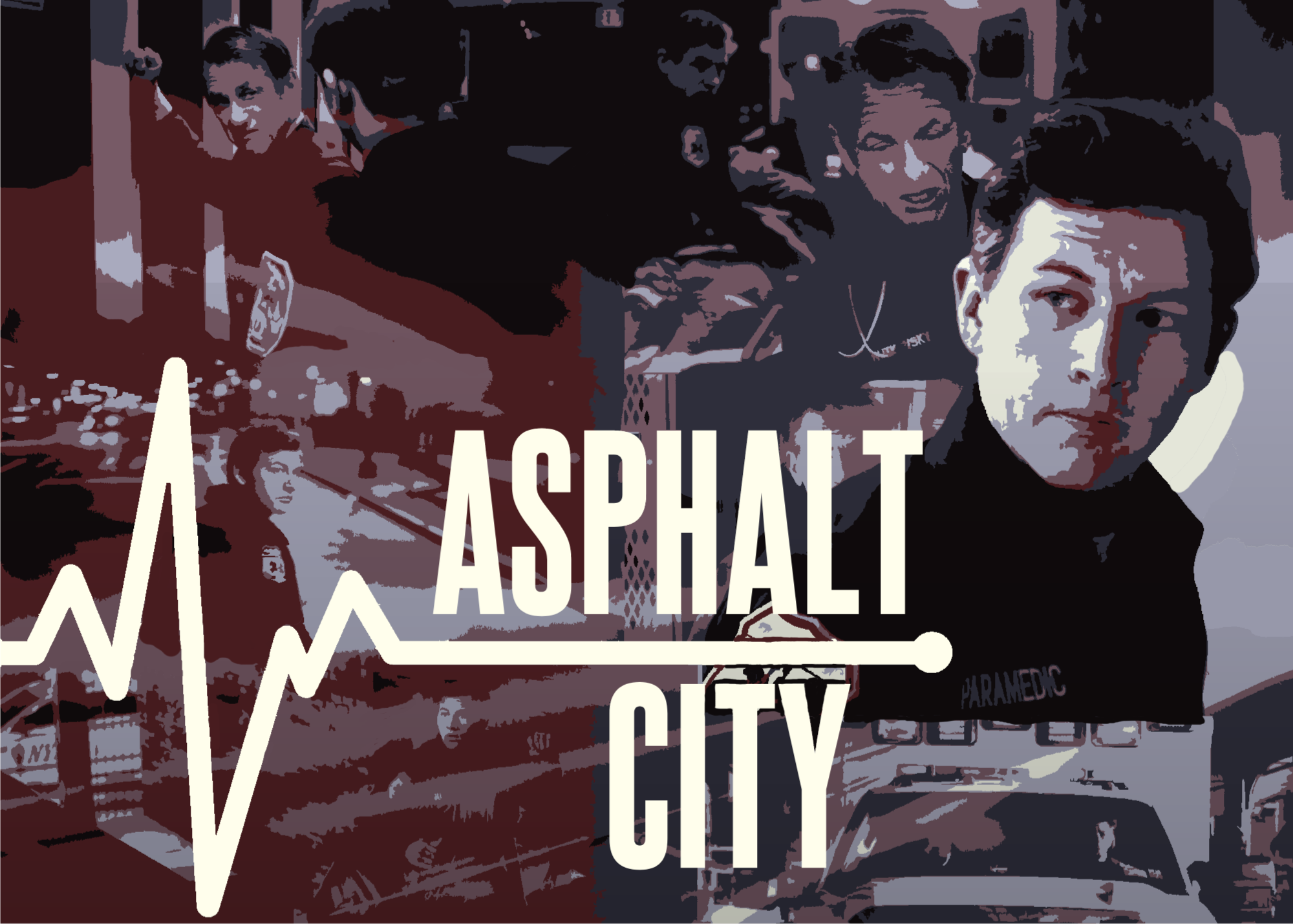

"Asphalt City" Review: A (Sort Of) Hard-Hitting Tribute to Medical Mayhem

It's not as profound as it believes, but strong performances elevate this EMS drama.

ModernAccording to a 2021 CDC article, EMS responders are 1.39x more likely to commit suicide than members of the general public. Occupational stressors in a psychologically taxing environment essentially create a powder keg; even if the detonation takes time, PTSD is common among both physical and telecommunication responders.

It’s a common sense reality of a little-publicized issue. We primarily focus on the people getting responded to, decrying the American mental health system, rising homeless population, or various drug epidemics, and rarely consider the individuals responding. Direct experience deserves consideration, but seeing it every day, especially watching those you try to help constantly slip through your fingers, is not easy.

Asphalt City thus takes on the difficult task of any career movie: impart the reality of an occupation onto an audience.

It tries this in many ways that work, though not as well as it believes, and many that don’t and never could have, even for those compelled by visual cues. Periodically, we see rookie paramedic and presumptive medical school graduate Ollie Cross in the passenger seat of an ambulance. The emergency lights fade into view as the scene transitions to Cross indulging the slightly parasitic sexual dynamic he develops with single mother, Raquel. It’s a visually transparent signal that his job’s emotional burden is seeping into his personal life, which the film makes clear without aesthetic gimmicks. As usual, style doesn’t add substance.

This misguidedness partially explains why Asphalt City struggles to illuminate the struggle of EMS responders and how that struggle inevitably manifests in long-term self-destruction and hopelessness. Sure, it technically illuminates because it’s a movie about precisely that, but does it do so well enough to impart a profound message? Eh.

Its chief failure is the lack of awareness regarding how connected we can feel. We each possess innate recognition of the bad. Regardless of knowing the individuals personally or having experienced the trials ourselves, we can see a drug addict thrashing in the back of an ambulance or a gunshot victim drawing his last breaths and understand the tragedy and severity.

A movie must transcend that to make an impact; if Asphalt City wanted to explore the harsh reality of being EMS, it needed to create compelling characters within an equally compelling narrative, space out a few particularly egregious calls, and fill the in-between with character development that would make us feel for the responders.

Tye Sheridan and Sean Penn are stellar, and the pair’s chemistry and individual exploration of Cross and veteran paramedic Gene "Rut" Rutkovsky, respectively, layers the movie with much-needed emotion, but they occasionally must raise Asphalt City from the dead. The movie wants us to care about EMS responders but doesn’t give us any worth caring about beyond a principle that a documentary would’ve better explored.

We never see (or even hear about) all of the weird sex toy or household appliance mishaps, implying that the profession is so mercilessly bleak and inescapably morose that the ultimate choices made by Cross and Rut are inevitable. Even if that incessant grimness was authentic, it would never feel so on-screen. Occasionally, one must temper reality to make it feel real. It may feel like a betrayal of the subject matter, but creators cannot control an audience's emotional comprehension.

Unfortunately, Asphalt City tempers nothing, so it reeks of the overabundance that helped ruin American Fiction. Writer Thelonious Monk’s family is in tatters: his father is long dead, his mother has Alzheimer’s, his sister dies of a heart attack, and his brother is a drug addict. It’s too much. Cross and Rut should never have walked into a dingy, New York City apartment to find some yokel with a football shoved up his ass, but the aura created by approaching the story with an obsessively gloomy worldview was not the way, either.

Why, then, is Asphalt City still a good movie?

Because, for all its faults, it gets enough things right to be an alluring watch that, despite not wholly dissecting the plight of EMS responders, compels us to do independent research and show ardent respect for those who observe and help people at their lowest, most dire circumstances.

Most films would have created a clichéd dynamic between Cross and Rut, positioning the former as the doe-eyed rookie and the latter as the jaded, emotionally vacant vet. Rut would've relentlessly dismantled Cross’ idealism, forcing him into a sobering acceptance and psychologically compelling him to make decisions he would’ve never considered. As Cross deteriorated, Rut would’ve gone insane, likely hooked on drugs or alcohol with incessant family troubles that consumed his screen time.

Instead, Cross, though new and thus technically green, never feels insincere. The soulfulness that sees him try to help a violent dog doesn’t feel naive, even as we reflect on it during the ending credits. It feels like a genuine design of someone fully aware of the concept of his job but intent on navigating it without compromising himself. Even as he sinks into the void, slowly corrupted to the point of nearly choking his girlfriend into a blackout during a domineering sexual encounter, that soulfulness still feels tangible.

Rut, for his part, is reasonably well-adjusted. He’s clearly somewhat worn down by the job, and his numerous divorces have left him the father of a daughter he hardly sees, but he’s not cartoonishly temperamental. The outbursts we see feel like an authentic result of the pressure cooker these men work in. When Cross looks on as Rut goes toe-toe with a domestic abuser, it feels sincere. Rut tried to reason with the man but got pushed past his limit. The core of someone who signed up to help people remains, so where most films would’ve turned Rut into an Alonzo Harris figure, Asphalt City achieves sincerity and nuance.

As such, the moments where Cross and Rut bond feel natural; when tension arises, the unease feels palpable. We don’t unnecessarily get each man’s entire backstory. Even if the pitstop to Rut’s old apartment to spend a few moments with his daughter seems hamfisted, the execution prevents it from feeling like a tag-on, like those insufferable scenes with Billy Beane’s daughter in Moneyball. The father-daughter dynamic is relegated to the background as Cross talks with Rut’s ex-wife, giving insight into Rut without feeling overwhelmed by sentiment. Meanwhile, Cross learns the personal impact of the job. By resisting full-blown cliché, Asphalt City gives itself flexibility and versatility.

We can’t ignore how it doesn’t fulfill its aspirations. Rut’s choice upon seeing the baby newly born to a drug-addicted, HIV-positive mother, which ultimately powers the climax, falling action, and resolution of the story, doesn’t feel earned. Why? Because Cross wouldn’t have made it himself. Rut’s decision comes after 15 years of experiencing what we’ve spent 90 minutes only observing; even the most skilled writers and actors couldn’t sell us on it in that amount of time. If the audience gives the benefit of the doubt, filmmakers must meet us in the middle, rewarding our suspension of disbelief with what is plausible within the movie's confines.

Common criticisms of Asphalt City ring false. Society has overcorrected to the point where any female nudity gets labeled "gratuitous." Arguably, despite an extended full-frontal look at Cross’ lover, a brief glimpse of his nethers, and multiple sex scenes, the movie needed more sex and nudity: the more explicit, the better.

The film pulls no punches when showing the horror EMS responders confront; visually, it’s one of the most unapologetic movies you’ll see. It should’ve given similar treatment to Cross’ coping mechanisms. He seeks vulnerability without the capacity to commit emotionally, partially because of his childhood trauma and partially due to his professional baggage. A more explicit, exposed display of this search for connection and reprieve, matched by an equally forward visual depiction of what he’s seeking to repress, would’ve strengthened the movie.

Some have called it overly morose and bleak. If one can’t stomach reality, even if exacerbated, one shouldn’t be watching movies.

Asphalt City's problem is that it spends too much time on its visual gimmicks and insistence on the overblown that, despite its successes, it cannot leave the impact it seeks. It lands in that vague in-between, the cinematic No Man’s Land.

It isn’t what it believes and makes foundational errors that render the dream an impossibility, but when it provides a showcase for Sheridan and Penn, along with a guttural visual perspective on New York City and the inhabitants who’ve hit rock bottom, it’s a fascinating movie that, if unable to shine a bright enough light on its subjects, at least makes us consider those we’ve overlooked in the mental health crisis.

67

Director - Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire

Studio - Roadside Attractions/Vertical

Runtime - 120 minutes

Release Date - March 29, 2024

Cast:

Tye Sheridan - Ollie Cross

Sean Penn - Gene Rutkovsky

Michael C. Pitt - Lafontaine

Gbenga Akinnagbe - Verdis

Mike Tyson - Chief Burroughs

Raquel Nave - Clara

Katherine Waterston - Nancy

Kali Reis - Nia Brown

Editor - Saar Klein, Katherine McQuerrey

Screenplay - Ryan King, Ben Mac Brown

Cinematography - David Ungaro

Score - Nicolas Becker, Quentin Sirjacq

%20(13%20x%206%20in)%20(13%20x%204%20in).png)

.png)

.png)